When founders think about valuation, it’s often in the context of raising money — negotiating with investors, calculating dilution, and pitching a compelling growth story. But there’s another important context where valuation comes into play: issuing equity compensation to employees.

At first glance, these two purposes — fundraising and employee stock issuance — seem to call for very different numbers. And indeed, they often result in dramatically different outcomes. In the U.S., the valuation used for employee stock options is often determined by a 409A appraisal, which can place the company’s worth at a fraction of its last fundraising round. But why is that?

The most common answer is incentives. But there’s more to the story.

In this article, we’ll explore why these valuations differ, how they are derived, and what founders need to understand about the theoretical and practical justifications for this divergence. While focused primarily on startup founders, this analysis should also interest early-stage investors and even auditors, especially as valuation standards continue to evolve.

The Incentives Behind Different Valuation Purposes

Let’s start with the most straightforward explanation: incentives.

When you’re issuing equity to employees, you want the strike price to be low. Why? Because equity is meant to be a reward — a stake in the company’s future success. If you issue shares at a $1 strike price, and soon after the company is valued at $5 per share, that’s already 5x in value for the employee. That’s powerful motivation.

But if the strike price starts at $5? That subsequent valuation event doesn’t increase the share value, and employees do not see their work translating into growth in value, damaging morale.

So it benefits everyone — the employee, the company, and even the tax authorities — for the strike price to be grounded in a fair estimate of current value. In the U.S., this is where the IRS-sanctioned 409A valuation comes in. It’s an independent appraisal meant to protect employees from receiving options that are later deemed underpriced by tax authorities. But it’s also a process that inherently leans toward caution, emphasizing current financial performance and downplaying speculative future growth.

Fundraising, on the other hand, is built on the opposite logic. You’re selling a vision, raising capital precisely so that you can achieve future growth. As a founder, you are incentivized to raise at a high valuation to minimize dilution (although not so high that subsequent growth in value will be challenging).

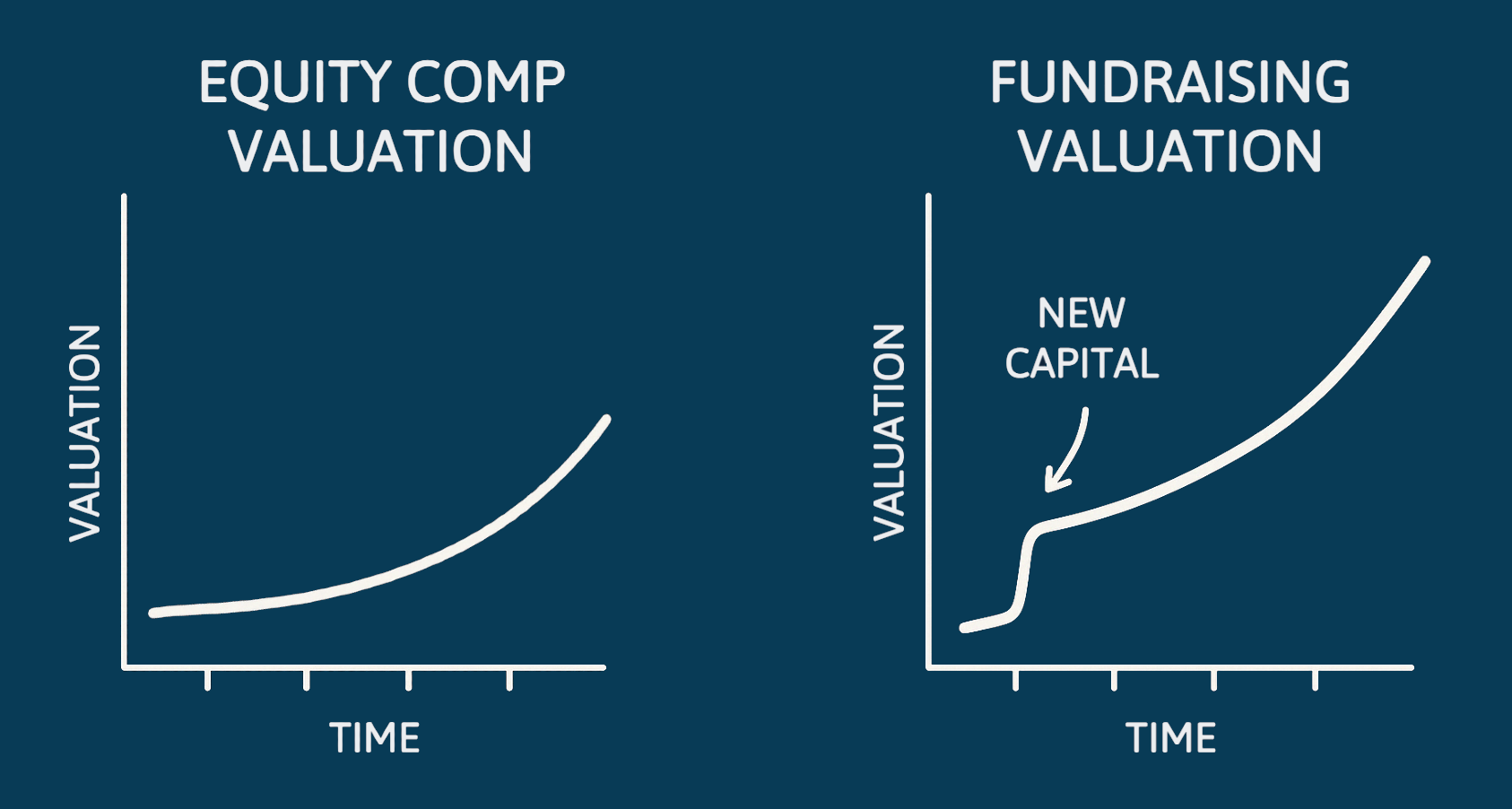

So the difference in incentives is clear: fundraising valuations are conditional; equity compensation valuations are conservative.

The Theory Behind Valuation: Shouldn’t a Company Be Worth What It’s Worth?

Now let’s go deeper.

A valuation is, at its core, a statement about what a company is worth today, based on expectations for the future. In theory, this should not vary wildly depending on why you’re doing the valuation — whether for issuing shares to employees, raising capital, or reporting to auditors. The company is the same, after all.

So why are these numbers so different in practice?

The answer is subtle but significant: the assumptions baked into the valuation scenario differ.

Fundraising Valuation Assumes Capital Injection

When you do a valuation for fundraising purposes, you’re not valuing the company as it stands today. You’re valuing what the company could become if it receives the investment.

This is a conditional valuation. For example, if you’re raising a $1M seed round, your forecast assumes that you will have that $1M to spend on hiring, marketing, product development, and so on. Those funds change the trajectory of the company — and therefore increase its value.

In this way, the fundraising valuation is not strictly a reflection of the company’s current state — it’s a reflection of that future scenario with the investment secured.

Equity Compensation Valuation Assumes Status Quo

By contrast, a 409A valuation (or similar equity compensation valuation in other jurisdictions) looks at the company as it is today. It assumes no capital injection. Just the current state of the business, extended into the future.

This naturally leads to a lower valuation. Without additional resources, growth is slower, risk is higher, and therefore the company is worth less.

This distinction is key, and it’s one that is often misunderstood, even among experienced founders and investors. But it’s crucial for legal, tax, and financial planning purposes — and it explains why valuation outcomes differ even when they’re both “fair” in their own context.

Preferred vs. Common Stock: Rights and Value

Another important reason why fundraising valuations tend to be higher than those used for employee equity compensation lies in the type of shares being valued. When institutional investors participate in a funding round, they typically purchase preferred stock. These shares come with a suite of rights and protections — the most notable being a liquidation preference, often 1x. This means that in the event of an acquisition or other liquidity event, preferred shareholders are entitled to receive at least their initial investment back before any proceeds are distributed to common shareholders. Preferred shares may also include voting rights, anti-dilution protection, board representation, information rights, and other terms negotiated during the funding round — all of which enhance their value relative to common stock.

By contrast, employee equity is almost always issued in the form of common stock, or options for common stock. These shares typically carry none of the protections of preferred stock. They are subordinate in liquidation, have no voting rights, and come with transfer restrictions that make them harder to sell in secondary transactions. Employees and even founders have less leverage, fewer liquidity options, and more exposure to dilution over time. For all these reasons, common stock is objectively worth less than preferred stock, and this differential should be reflected in any fair valuation. Accordingly, 409A valuations (and similar appraisals in other jurisdictions) are based on the value of common stock, which further explains why they tend to be significantly lower than the valuations used in fundraising rounds.

A Note on Pre-Money and Post-Money Valuation

Another area of confusion arises around the terms pre-money and post-money valuation.

It’s commonly assumed that:

- Pre-money valuation = value of the company before investment

- Post-money valuation = value after investment (i.e., pre-money + amount raised)

But this framing is misleading.

In reality, the pre-money valuation already reflects the anticipated impact of the investment — in terms of future growth, execution, and market capture. What it doesn’t include is the cash itself. The cash is simply added on top to get the post-money figure.

This matters because it underscores that the entire fundraising valuation is conditional — it presumes the capital will be raised and will generate a return. Strip away that assumption, and the valuation logic collapses to something closer to what you see in a 409A.

Practical Implications for Founders

1. Understand the Purpose of Your Valuation

Are you fundraising? Issuing employee stock? Reporting to investors? Filing taxes?

Each use case has different requirements, assumptions, and consequences. Always start by being clear about the purpose — and communicate that to any advisor, platform, or valuation provider you’re working with.

2. Don’t Mix Valuation Logics

Never use your fundraising valuation as the basis for issuing employee options. It may look better on paper, but it creates serious risk — particularly in jurisdictions like the U.S., where the IRS can retroactively reprice options and impose tax penalties.

3. Use the Right Tools

Platforms like Equidam allow you to tailor the valuation logic to the purpose. If you’re fundraising, fill in the Funding tab — and model how the capital will be used in your projections. If you’re doing a compensation valuation, leave it empty — and value the company as it stands today.

This distinction ensures you get a realistic, compliant result for the specific context.

4. Anticipate Scrutiny

Auditors, regulators, and even LPs (in the case of VC funds) are increasingly pressing for transparency and consistency in valuation practices. It’s no longer enough to simply declare a number and move on. The logic and assumptions must be defensible.

Final Thoughts: One Company, Many Values

In finance, it’s easy to think that a company has a single, true value — like the price of a stock on a public exchange. But in the private startup world, valuation is more fluid. It depends on what you’re valuing, when, and why.

For founders, understanding these nuances isn’t just about compliance — it’s about strategy. Knowing how to structure your equity plans, communicate with investors, and set expectations internally all flow from this basic understanding.

And for investors and auditors, this clarity helps ensure that incentives are aligned, risk is managed, and decisions are made on solid ground.