Multiples are the cornerstone for understanding the share pricing for companies of all sizes, from pre-seed startups in emerging sectors, to the largest public companies in legacy industries.

They’re most well known for pricing analysis on publicly traded companies, where investors will use multiples for comparative analysis. Imagine comparing products in the supermarket, where different box sizes and a range of pricing may make it hard to determine the value; labels that give you the price per kg of product can greatly simplify that process.

Looking at a range of possible multiples (such as EV/revenue, EV/EBITDA, EV/FCF or P/E), investors can compare the price of equity against revenue performance, financial health, and growth expectations, in an attempt to find under-priced opportunities. For public companies, this is made easier by reporting requirements for financial information, as well as the liquid nature of those shares — meaning the current share price is always known.

For private companies, it’s a whole different ball game.

The usual case for private company multiples, and why it never happens

Valuing private companies, especially early stage private companies, is notoriously tricky. A shortcut that many investors attempt to use is to apply a multiple.

In the perfect scenario…

- the investor can find a number of similar companies (similar traction, growth rate, exit potential),

- that have raised capital recently (similar market dynamics),

- from which they can determine a reasonable average revenue multiple (if they have access to financial information and round pricing for all of those companies),

- so they can apply that multiple to stable, meaningful revenue, providing a quick and easy way to price the round.

In reality, this fails on a number of fronts. Startups are by nature fairly unconventional, so finding similar companies is always a struggle. Their growth is volatile, so it’s not always clear that current revenue is a meaningful metric. Add the additional constraints on timeframe and access to the relevant data, and it’s virtually impossible to determine a useful multiple. Unfortunately, these complexities don’t stop investors commenting on multiples for AI or deeptech startups as if they were all in the same ballpark as a generic SaaS business.

So, it turns out that the real application in private markets is enabling investors to quickly justify the pricing they were already aiming for with some multiples-based trickery — which recent history tells us will often end in a procyclical tailspin.

How we use multiples in valuation

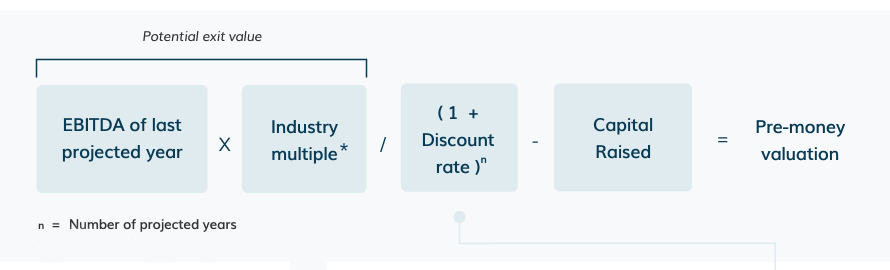

Despite the myriad of issues with applying multiples to private company valuation, they do still add a valuable perspective to understanding the worth of a company. Specifically, in understanding the exit potential of a company, by applying a multiple to the terminal value (the last year’s projected EBITDA or revenue).

This is distinct from trying to calculate the entry multiple (the price of the investment round), where multiples are attempting to establish a market-based price through comparison to similar companies.

This approach has a number of benefits:

- It allows us to use public company multiples, where there is no challenge finding reliable, current data. This can be via the industry average multiples on our platform, or through building a list of public comparables (as described in this article by Scott Kupor of Andreessen Horowitz).

- It provides a more useful reflection of market potential at exit, by understanding the performance of public companies in that category. This is more useful than trying to establish current pricing, as the ultimate outcome always depends on the exit.

- By applying the multiple to the terminal value of revenue or EBITDA, it provides a specific reflection of the ambition and vision of the founder, rather than a simple price by comparison. This better reflects the outliers and exceptions that venture investors are trying to find.

This also explains why we default to using EBITDA multiples (though revenue multiples may be used via the Advanced Multiples section): in understanding the exit potential of a company, we must also better understand the financial health through profitability.

Benchmarking with multiples

There is one other use for multiples, which is in line with the way that they are applied to public companies: benchmarking company value with revenue or EBITDA. In this case, we are looking at multiples purely as another lens on the startup — to understand how it compares to others.

These benchmarks allow you to compare a startup with multiples providing a number of different comparative perspectives:

- …to the range of public company multiples you’ve selected

- …to historical multiples for that industry

- …to other companies at that stage of development

- …to the public markets as a whole

With this approach, we can offer both private company multiples (stage multiples) and public company multiples (the rest) as a means for adding context to valuations, rather than simply an input into the process.

You can read more about our benchmarking with multiples in the associated helpdesk article, where we’ve also published some more detail on the reference multiples we use.

Final thoughts about the application of multiples to startup fundraising

A fundamental truth is that startup investment is a game of finding outliers. The hunt is always for that one exception, the one company in fifty that has the potential to ‘return the fund’. This is why it’s important to use multiples in a way that doesn’t just simplify pricing to an average. You have to let the specific opportunity express itself through the valuation process, to have a better shot at identifying those startups.

It’s also important to base your process on reliable data, so that you can trust the outcome — rather than using questionable data and then just using your gut to verify the outcome. The former is a genuinely useful input into the valuation process, while the latter is just an excuse to be lazy with pricing and reinforce your intuitive (biased) decision-making.

If you’re going to use multiples as a part of your investment decision making, it is important to understand their purpose:

- For private company multiples, using rough data on peers, the purpose is providing context to a valuation which also reflects current market dynamics.

- For public company multiples, using data from mature companies with much slower growth, the purpose is understanding the eventual exit potential.

In neither case is the purpose to determine the entry multiple for an investment. The entry multiple is an output of the process, not an input, as described by Alex Immerman and David George of Andreessen Horowitz:

“If a company is expected to be very valuable on a probability-weighted outcomes basis, the investor can afford to pay a higher entry valuation, and implicitly, a higher entry multiple. In other words, the ends (like the possible exit values) can justify the means (a seemingly higher present-day valuation).”