There’s no shortage of content covering startup fundraising advice, whether it’s solidifying your valuation or financial projections, or timing your fundraising sprints. Founders can follow a pretty solid roadmap once they decide to pull the trigger, but how do you know when the time is right?

In this article we’ll look at a few of the often-overlooked factors which might inform when to raise capital for your startup, and how much you might look to raise.

12 Months w/ 50% cushion = 18 months

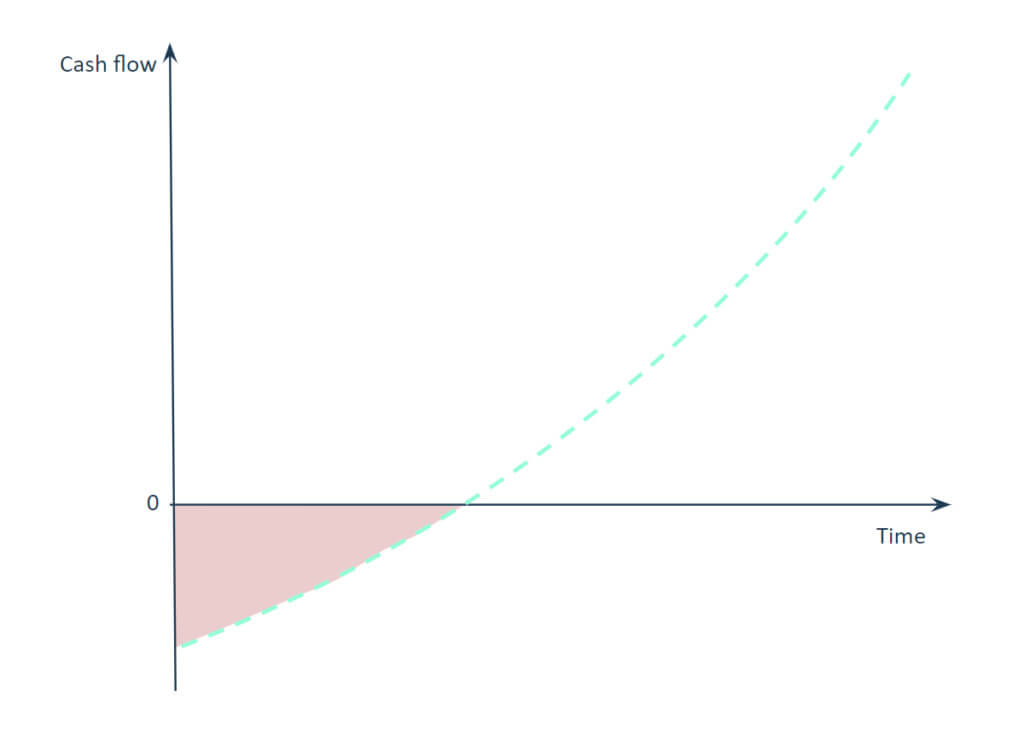

You’ve done your financial projections, and you’ve worked out the amount of negative cash flow you’ll need to cover until you can achieve your next milestone. It’s too much to go asking friends and family, and too much to take on as credit-card debt. Fortunately you’ve planned far enough in advance that you can spend a little time building your fundraising strategy and getting the timing right.

Should you raise all the capital you’ll need at the beginning? You would save the time and headache of raising multiple rounds. But raising sooner means raising at a lower valuation, giving away more equity, reducing motivation and leverage for the future.

Should you raise all the capital you’ll need at the beginning? You would save the time and headache of raising multiple rounds. But raising sooner means raising at a lower valuation, giving away more equity, reducing motivation and leverage for the future.

Why not raise small amounts regularly, as you need them? That might be the most efficient, equity wise, but you waste a lot of time and energy which should be invested into building your company and generating revenue.

A standard amount of capital to raise at seed stage is 12 months of runway with a 50% cushion – so 18 months of runway is the rule of thumb. You will need to look at your financial projections, understand how costs and revenue will compete as you build the business, and how much negative cash flow you’ll need to cover.

18 months is a very broad average, not covering every scenario, but it’s a helpful place to start.

Having said that, this should almost always be adjusted for the following reasons:

- Industry

- Milestones

- Calendar

- COVID

- Hype

- Growth

Fundraising according to Industry

Industry is perhaps the most obvious factor in how much you will need to raise, and when you’ll need it.

Different industries are going to need different amounts of capital at different moments in time. Software is traditionally quite cheap to start out, but costs scale over time as feature sets and maintenance demands grow. This results in lower-risk businesses which is why the software sector has long been a favourite for investors.

On the other hand, hardware companies need a lot more up-front capital to cover setting up production. Similarly, Pharmaceutical companies need quite a lot of up front capital for R&D and clinical trials. Games companies are an example where traditionally almost all of the investment is up-front, and all of your money starts to show up on release day. These companies obviously represent a bigger upfront risk to investors, but are also less easily displaced by younger startups, once established.

These three industries are examples where the founders may end up with less equity, as they are forced to raise more money at an earlier stage when the risks are higher and the potential is not yet proven.

Fundraising according to milestones

You might feel tempted to raise capital to enable you to reach a milestone. For example, you may want funding for the launch of your online store, where you can then generate some initial revenue and prove that customers want to buy your product. Unfortunately your investors are unlikely to look at it quite the same way.

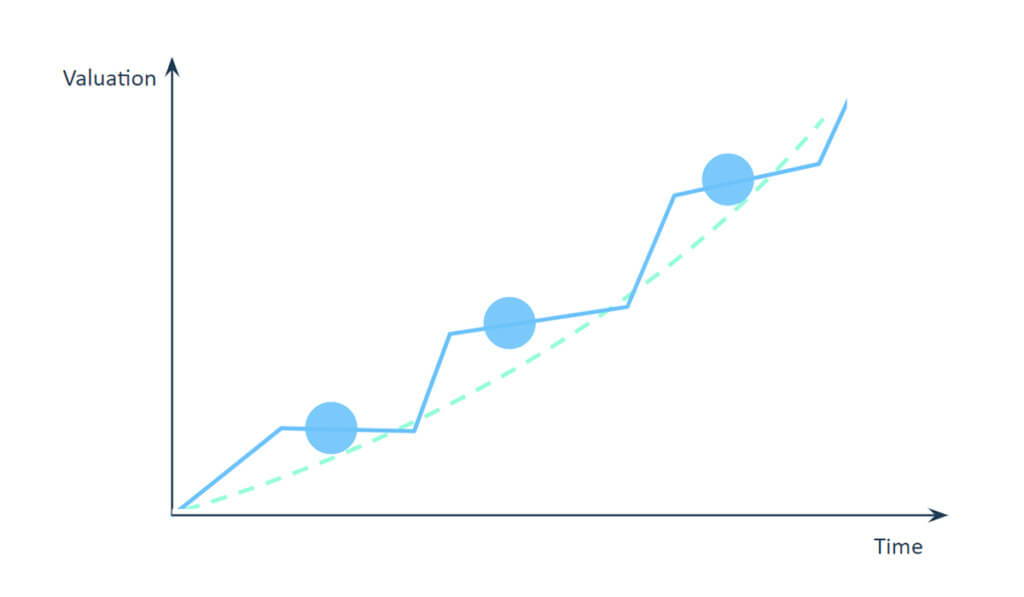

Valuation is increased as you prove more of your assumptions. You need to be able to test your plan and demonstrate solid reasoning with results. One of the most obvious ways to do that is to already have customers, with the revenue and the data they provide, before talking to investors. So raising after a milestone is obviously more attractive, in combination with a well-considered roadmap of future milestones which build on what you’ve proven up to that point. .

The name for this approach is ‘island hopping’. You raise enough money to hop over to the next island where you can hit the next milestone, which you can then use to raise further capital to get to the next island. The main consideration here, when starting out, is that you can bootstrap to that first major milestone – or perhaps rely on capital from friends and family or business grants to get you there.

The name for this approach is ‘island hopping’. You raise enough money to hop over to the next island where you can hit the next milestone, which you can then use to raise further capital to get to the next island. The main consideration here, when starting out, is that you can bootstrap to that first major milestone – or perhaps rely on capital from friends and family or business grants to get you there.

Fundraising according to calendar

There are basically two fundraising periods during the year: a winter window of September to December, and a longer summer window of January to July. These can vary a bit depending on the traditions and holidays in each country, but these waves are evident in our data and in data from other sources looking at startup fundraising.

Put simply, if you are thinking of starting your fundraising in October, you need to be very confident that you can close that deal before the end of the year. You’ll need to have everything ready, including your research on the right investors and how to approach them, and be fairly sure that the round will move quickly without any nasty surprises for either side. If you have a simple business model with some clear growth data that is backed by industry trends, this might be doable.

A safer bet, which provides you more scope for getting the best possible terms for your deal, might be to spend some time getting everything lined up for a more thorough and considered fundraising campaign kicking off early in January.

Fundraising according to COVID

If you observed the general public sentiment during the pandemic, you might have noticed that it produced waves of panic in addition to waves of optimism. These were reflected in the data on fundraising activity for startups, for obvious reasons.

As a founder, of course you want to try and raise capital during a wave of optimism, when everyone feels good and the future looks bright. Generally speaking those waves appeared at the beginning of each year, as we approached summer, rather than afterward as we looked toward bad weather and another flu season. The timing of events like the vaccine rollout, as well as the appearance of new variants, has also played into this, and they generally emphasized the ‘start of a new year’ optimism.

It also seems that the more experienced, confident and ambitious founders seem to be able to recognise these waves of optimism, and were better prepared to move quickly and capitalize on those moments.

Fundraising according to Hype

You don’t need to go far to see evidence of the Web3 hype at the moment – as a current, topical example – and there is certainly a significant element of hype to fundraising. It contributes to valuations and the pace of deals being made, as investors rush to make sure they secure their piece of the pie. Even seasoned investors aren’t immune to a little FOMO.

That said, if you are trying to follow these trends with your business, you are almost certainly going to be too late. The people who are raising money now with Web3 related companies probably started work on building two or three years ago, and had some existing background and expertise in that technology.

It might be worth considering – for other sectors – whether you are building in a sector that has the potential to strike a chord with investors and customers in such a manner further down the line, or perhaps you can find a way to attach what you are doing to another existing trend. For example, some of the ‘distributed ledger technology’ applications which might have fared better from a fundraising and adoption perspective had they launched a little later under the ‘blockchain’ moniker.

Adjustment according to growth

For some startups the pace of fundraising might be influenced by the pace of growth in their market. This is specifically the case for B2C companies who achieve the first-mover position in a hyper-competitive market, and then have to maintain that edge through outspending their competition to fuel growth.

There’s a few notable examples of this strategy, some making a better case for it than others. Uber, perhaps the most obvious, was doing at least two large funding rounds a year between 2012 and 2018 and developed a reputation for their incredible burn rate. A more recent example would be the rapid grocery delivery market, which has become synonymous with throwing huge sums of money at customer acquisition.

These companies will be looking to raise roughly every 6 months or so if they are focused on hyper growth, at which point fundraising has to be a real core competence of the founding team – with a CFO or founder dedicated to that purpose.

Conclusion

There is no magic wand to understand what the future will bring. And estimating timing and amount of fundraising feels like it requires one. The most important takeaway though is that it is a tradeoff, between raising larger amounts less often for more equity, or raising more frequently – optimising the equity but increasing the distraction time dedicated to fundraising.