Being a VC is not easy. It’s one of the few jobs with minimal feedback on your performance for up to a decade at a time. You screen a tremendous number of startups, pick a handful, and hope a few of those will grow up to become unicorns. Your job is to pick well, but the results of your selection aren’t apparent until many years later.

You are asked to estimate how well a startup will do, in order to ascertain a fair and attractive price – while knowing that being left out of one or two potential trillion-dollar deals could cost you your job later on.

It’s no surprise that prices are difficult to set. We can look back at valuations and round sizes in 2021 and say that they were exaggerated. But what brought about those excesses, and why wasn’t it clear at the time?

It feels like an eternity ago, but the last surge of the Covid-19 pandemic, the Omicron variant, was just last winter, 8 months ago.

There was no war, the supply chain crunch was limited to graphic cards and chips. Crypto, Robinhood, and Klarna were all the rage, and almost any investment made 2 years prior had achieved significant returns. We had just about pulled through a pandemic, and were starting to see the end of it. Euphoria.

The pandemic had another effect: it taught most people to live digitally. Thank goodness for technology, the singular force which allowed us to stay connected during the pandemic.

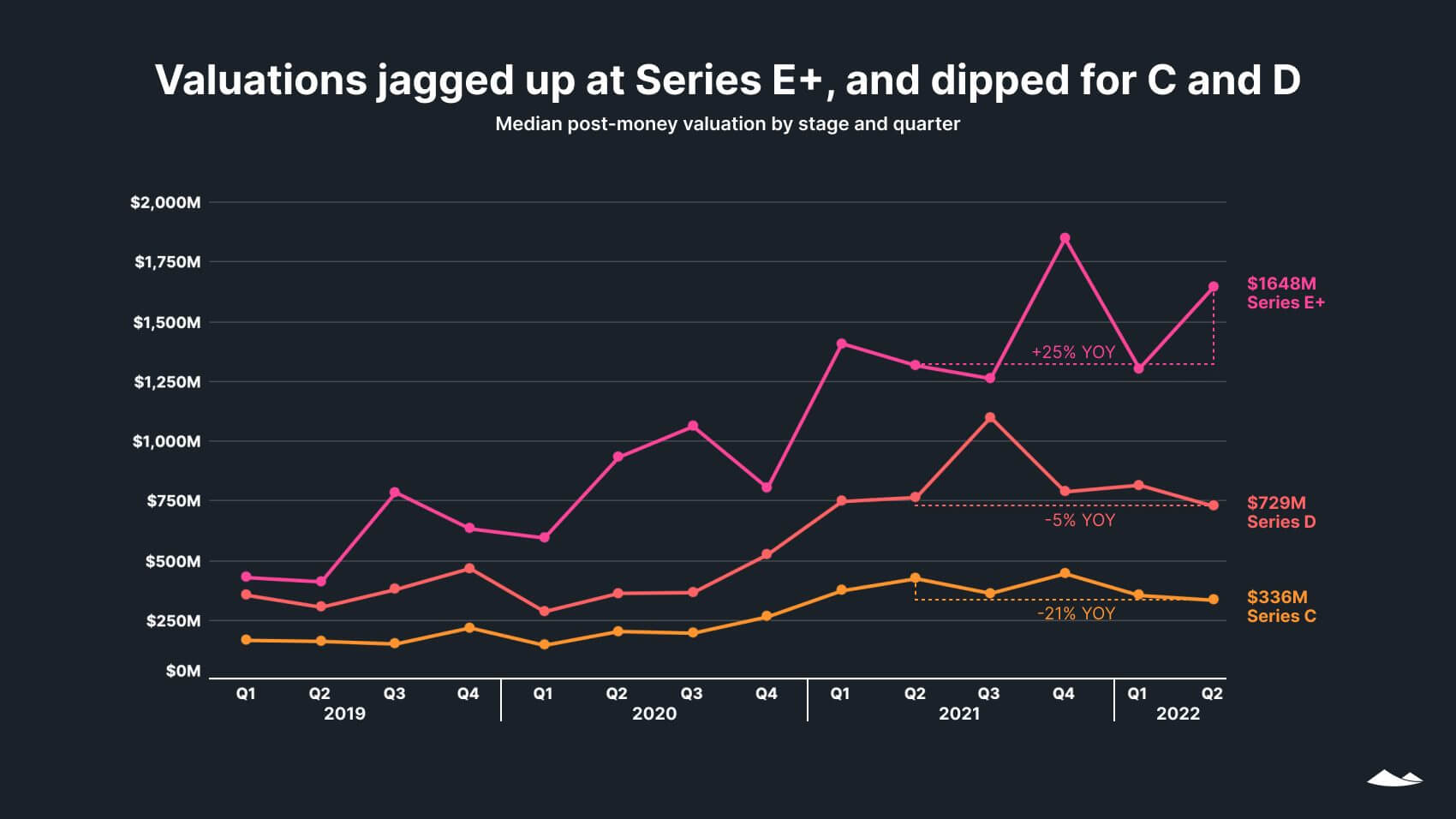

It is no surprise then that startups, the torch bearers of the digital Olympics, were reflecting these emotions in their valuations. Analysis from Carta tells a part of that story.

What they don’t show is the number of very large deals closed in record amounts of time, with minimal due diligence. The speed at which capital was deployed probably should have indicated that this was not sustainable.

Had investors lost sight of the ball? Have they forgotten about the fundamental “buy low, sell high” rule? If so, how could that happen?

Reason 1: The difficulty of price setting

Fast forward 10 months, and we have a much better understanding that price and value are disconnected. We have rediscovered the woes of inflation; painfully aware that something that costs $5 today may not cost $5 tomorrow.

This serves as a reminder that prices are not a property of the object, they don’t depend on anything physical, just supply and demand. At the intersection of physical and monetary, prices depend on two supply and demand curves: the supply and demand for the product or service, and the supply and demand for money.

These intersections are hard enough to set scientifically for everyday objects such as a loaf of bread or a can of Coke. They become extremely difficult when we are talking about the unique, volatile, and forward-looking prices of startup shares.

As with any price, startup valuations are set comparatively. Investors are compensated for the lack of certainty, the inherent risk in the return they predict. The best way to understand that risk to reward ratio is by looking at the rest of the market.

Comparisons can be made crudely, easily, or they can be made in a more refined manner. There lies all the difference.

When we look for a basic commodity at the supermarket, we can directly compare pricing with other products in the same category and consider the value of the differentiators that are promised.

For startups, it’s not that easy. Their innovative nature implies a lack of comparable companies, and the few relevant examples may have no price indicated, a false price, or pricing that is heavily influenced by market hype.

It’s easy to take the shortcut of making a crude comparison and calling it a day. As we’ll see in the upcoming points, there is both a theoretical justification for it and sufficient abundance of capital to not stress over the consequences.

Investors that looked deeper saw that it was very difficult to justify valuations in the post-Covid boom. Even with the most optimistic economic outlook, the new-found enthusiasm for digital products, and the large amounts of capital, something had to give.

Reason 2: New theories and players in VC gave the theoretical excuse

For the past 5 to 10 years, the VC world has been redefined by huge late-stage funding rounds. These large capital deployments originated from two funds: Tiger Global and Softbank Vision Fund.

Backed on one hand by large institutional money and on the other by the strong will of its founder, these funds reoriented the VC landscape with a new theoretical framework: the digital economy was still far from reaching its full potential, and vast sums of money deployed quickly could be differentiators for startups in winner-take-all markets.

Their speed of execution forced traditional VCs to adapt or be left out of the best deals, releasing the valve on valuation and increasing the throughput of the capital.

Reason 3: Vast amounts of capital with no parking zones

Thanks to MMT, governments have a morally easier time increasing deficits and the supply of money. Faced with the unknown depth of a pandemic, they built on the lessons of the last financial crises and subsidized the economic dip to shield the population from economic meltdown. This was mostly a success, and limited the damage of Covid-19 as much as possible.

Coupled with the difficulty of putting money directly in consumers’ hands, and the impracticality for consumers to spend the money due to lockdowns, this created vast amounts of financial capital that had to be invested somewhere. The IPO market surged to new record highs as companies scrambled to raise capital from the public market at never-before-seen valuations. Real estate, crypto, equity, bonds, and commodities were all riding high.

There were few attractive avenues left for the vast amount of capital that needed to be invested somewhere.

The strongest remaining proposition sounded something like this: “Because of Covid-19, the world has changed, digital adoption has accelerated and the sector will be some orders of magnitude bigger”.

This still rings true, and it probably is, just not at the magnitude that these bets were implying.

How we invest shapes our future

These three reasons contributed significantly to the separation of startup prices from their true value. They created overfunding for some opportunities, underfunding for others, poor returns for some funds, and big questions for a lot of employees.

If George Soros’ theory of Reflexivity ($), where investor’s sentiment doesn’t just track fundamentals but actually affects them, is even partially true, then how we choose, as a society, to allocate investment will affect not only the fortunes of those companies but also the direction of our future.

Startups are the breeding ground of future innovation. When we lose sight of the connection between price and value – and allocate large investments based on hype instead of fundamentals – we are wasting time, resources, and opportunities on the wrong problems, at a moment in history where help on the right problems is needed more than ever.